Chap 10 HW

1. Vocabulary

Deformable Body Mechanics

The study of how solid bodies deform under applied forces, combining principles of mechanics and material science. It includes analyzing stress, strain, and material behavior under load.Stress ($σ$)

A measure of internal resistance to deformation, defined as the applied force per unit area within a material (units: Pascals, Pa).

Formula: $ \sigma = \frac{F}{A} $ (where $ F $ = force, $ A $ = cross-sectional area).Strain ($ε$)

A dimensionless measure of deformation representing the relative change in shape or size of a material due to applied stress.

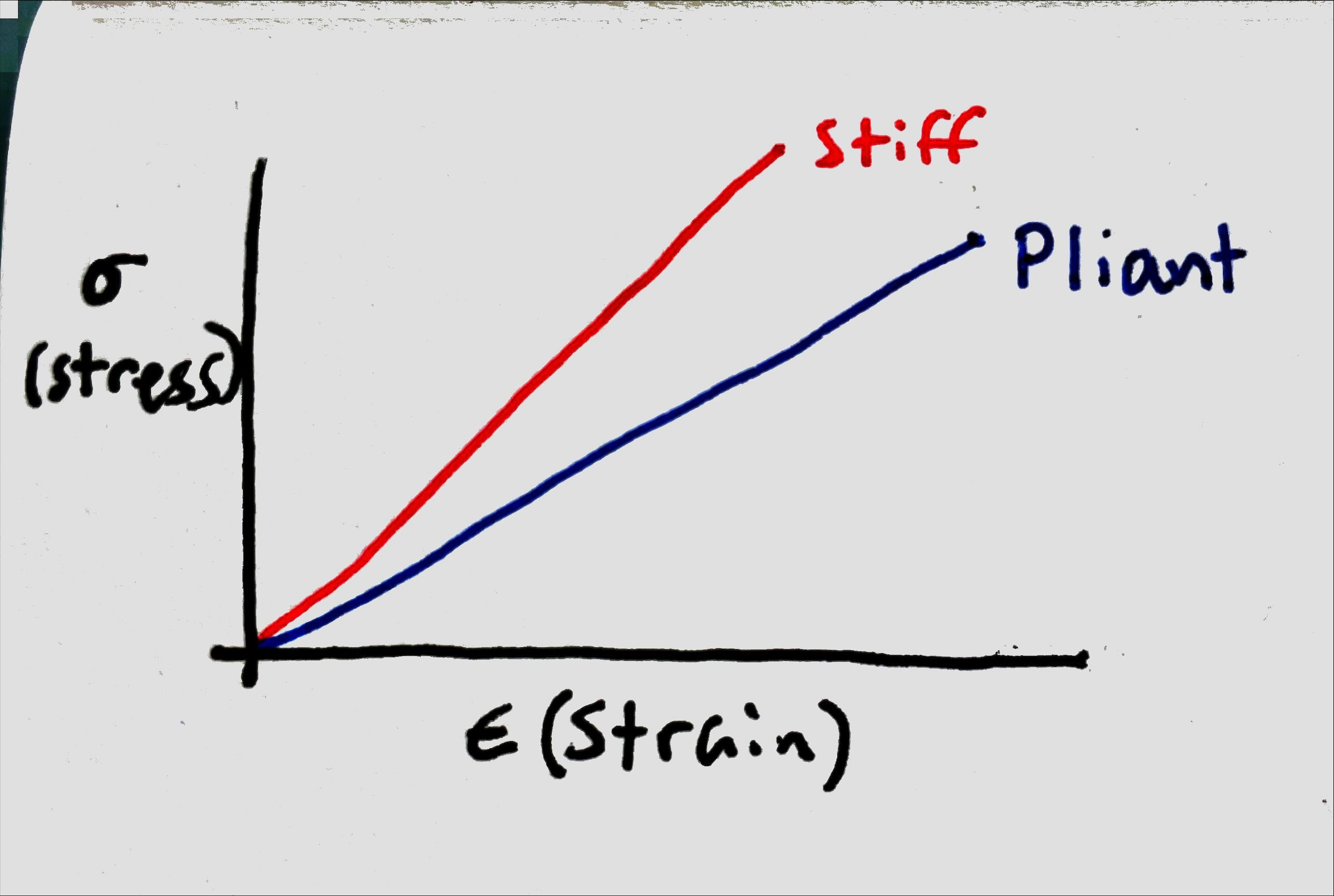

Formula (Axial Strain): $ \epsilon = \frac{\Delta L}{L_0} $ (where $ \Delta L $ = change in length, $ L_0 $ = original length).Stiffness

A material or structure’s resistance to deformation under load. It depends on both material properties (e.g., Young’s Modulus) and geometry.

Formula (Axial Stiffness): $ k = \frac{EA}{L} $ (where $ E $ = Young’s Modulus, $ A $ = cross-sectional area, $ L $ = length).Young’s Modulus ($E$)

A material property describing stiffness in the elastic regime, defined as the ratio of stress to strain (units: Pascals, Pa).

Formula: $ E = \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon} $.Anisotropic

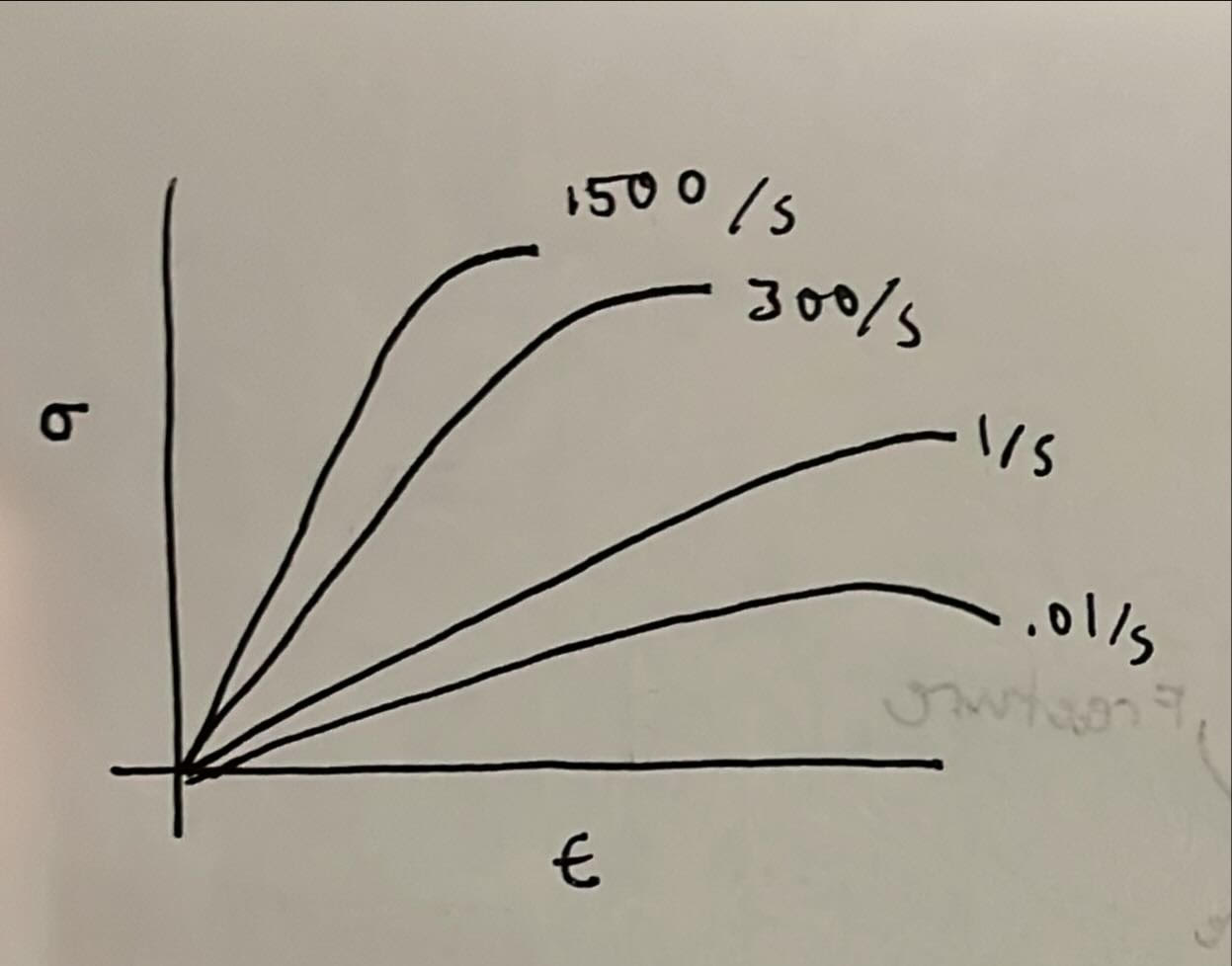

A material whose mechanical properties (e.g., stiffness, strength) vary depending on the direction of loading (e.g., wood, composites). Opposite of isotropic (uniform in all directions).Viscoelasticity

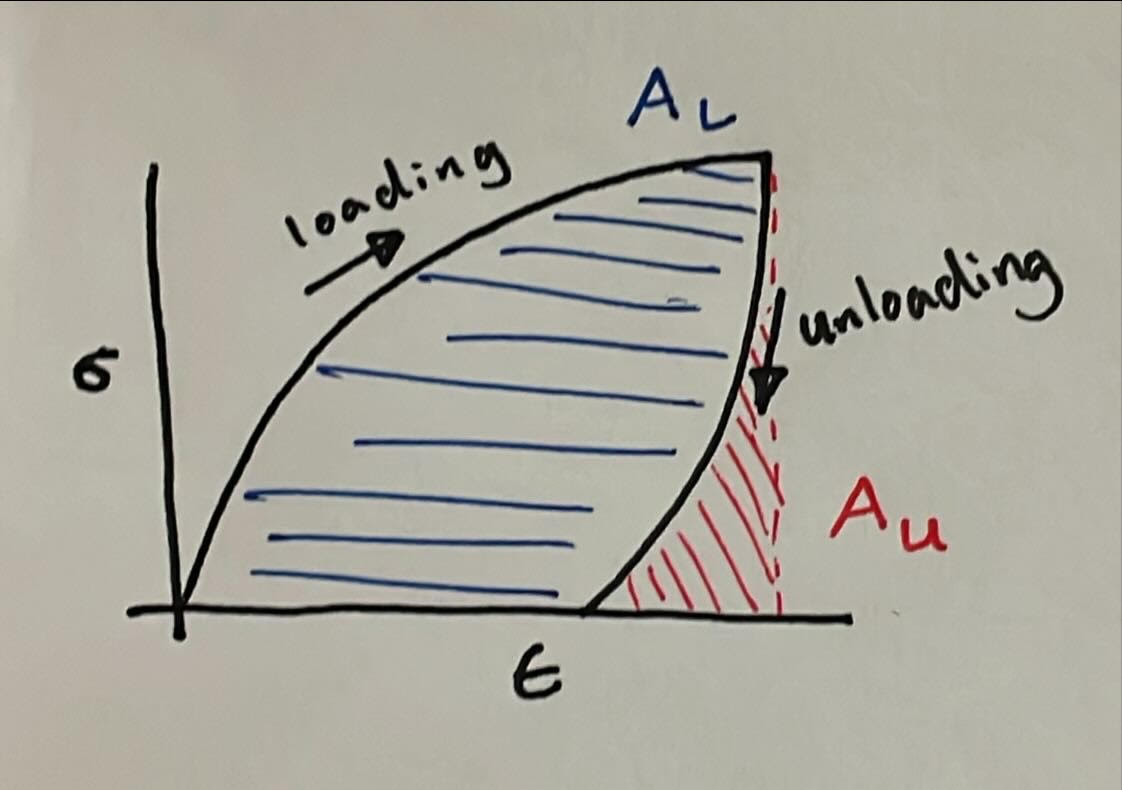

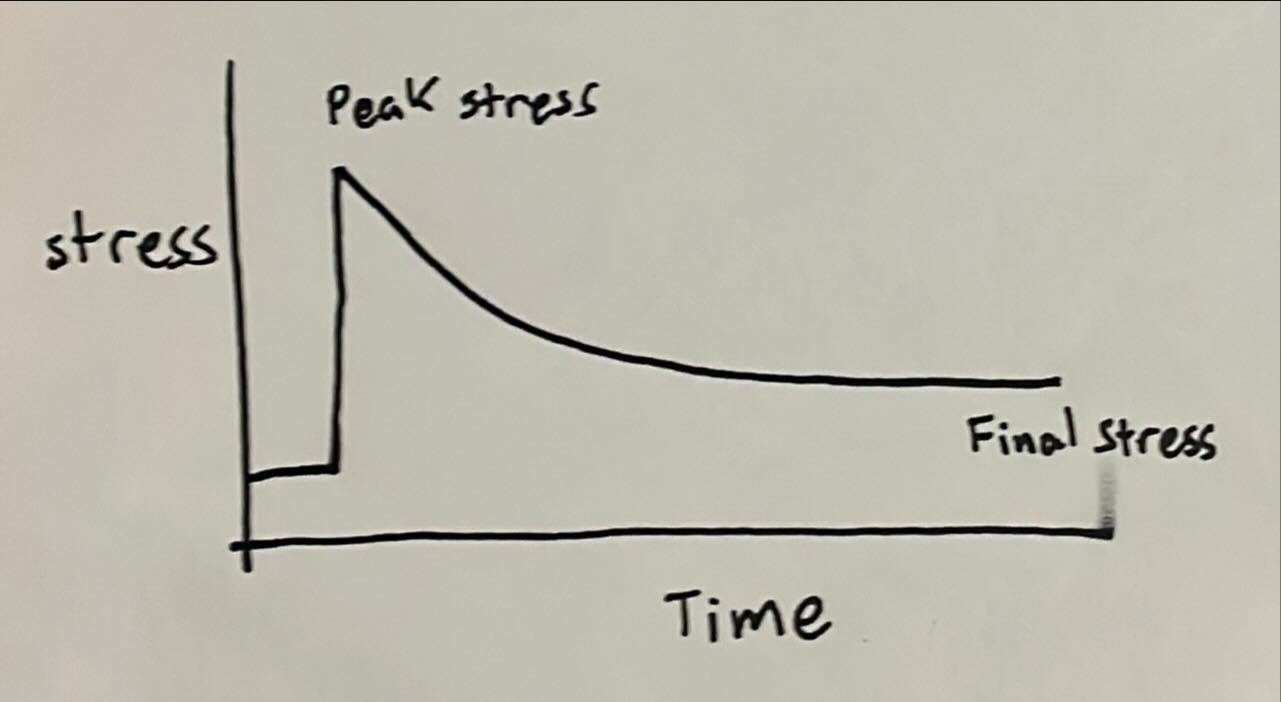

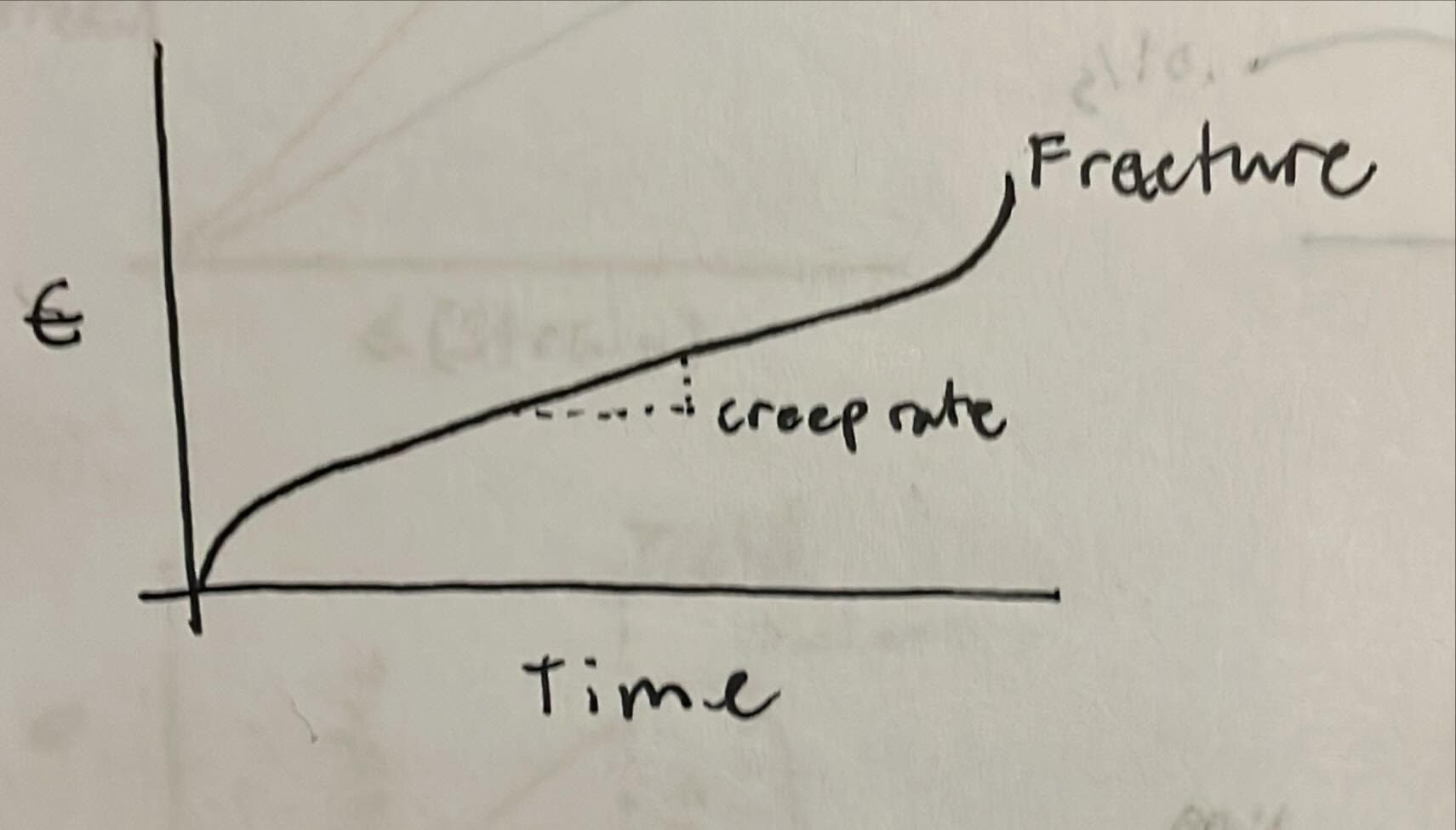

A material behavior combining viscous (fluid-like) and elastic (solid-like) responses, leading to time-dependent deformation (e.g., creep, stress relaxation). Common in polymers and biological tissues.Hysteresis

The energy loss (as heat) during cyclic loading and unloading of a material, represented by a loop in the stress-strain curve. Common in viscoelastic and plastic materials.

2. Formula Central

The amount of stress an object experiences when a force is applied:

$$

\sigma = \frac{F}{A}

$$

Variables:

- $\sigma$ (Stress): Internal resistance per unit area (Pa or N/m²).

- $F$ (Force): Applied external force (N).

- $A$ (Area): Cross-sectional area over which the force is distributed (m²).

Stress measures how concentrated a force is within a material. While pressure measures external force per area, stress measures internal force per area — they both use the same units. Higher stress means increased chance of deformation or failure.

The amount of strain within a material as it is elongated:

$$

\epsilon = \frac{\Delta L}{L_0}

$$

Variables:

- $\epsilon$ (Strain): Dimensionless measure of deformation.

- $\Delta L$: Change in length (m).

- $L_0$: Original length (m).

Strain quantifies how much a material changes shape. A higher strain means more deformation.

The stiffness of a material:

$$

k = \frac{EA}{L}

$$

Variables:

- $k$ (Stiffness): Resistance to deformation (N/m).

- $E$ (Young’s Modulus): Material stiffness (Pa).

- $A$ (Cross-sectional Area): Influences load distribution (m²).

- $L$ (Length): Longer objects are less stiff.

Stiffness depends on both material ($E$) and geometry ($A$, $L$). A higher $k$ means the material resists deformation more.

The Young’s Modulus of a material:

$$

E = \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon}

$$

Variables:

- $E$ (Young’s Modulus): Intrinsic material stiffness (Pa).

- $σ$ (Stress): Applied force per unit area.

- $ε$ (Strain): Resulting deformation.

Measures how easily a material stretches under stress. Higher $E$ means more intrinsically stiff.

The Work-Energy Relationship:

$$

W = \Delta KE + \Delta PE + \Delta U

$$

Variables:

- $W$ (Work Done): External energy input (J).

- $ΔKE$ (Change in Kinetic Energy): $ \frac{1}{2}mv^2 $.

- $ΔPE$ (Change in Potential Energy): $ mgh $.

- $ΔU$ (Change in Internal Energy): Heat/deformation losses.

Work done on a system changes its kinetic, potential, and internal energy (e.g., stretching a spring stores elastic energy).

Conservation of Energy applied to a ball dropping from height:

$$

PE_{\text{initial}} = KE_{\text{final}} \quad \Rightarrow \quad mgh = \frac{1}{2}mv^2

$$

Variables:

- $PE = mgh$: Potential energy at height h.

- $KE = 1/2(mv²)$: Kinetic energy at impact.

Energy converts from potential to kinetic as the ball falls (ignoring air resistance).

Power Output:

$$

P = \frac{W}{t} \quad \text{or} \quad P = F \cdot v

$$

Variables:

- $P$ (Power): Rate of energy transfer (Watts, W).

- $W$ (Work): Energy expended (J).

- $t$ (Time): Duration (s).

- $F$ (Force): Applied force (N).

- $v$ (Velocity): Speed of motion (m/s).

Power measures how quickly work is done (e.g., lifting weights faster requires more power).

Summary Table

| Concept | Formula | Key Variables | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | $ \sigma = \frac{F}{A} $ | Force (F), Area (A) | Force concentration in material |

| Strain | $ \epsilon = \frac{\Delta L}{L_0} $ | Length change (ΔL), Original length (L₀) | Deformation relative to size |

| Stiffness | $ k = \frac{EA}{L} $ | Young’s Modulus (E), Area (A), Length (L) | Resistance to deformation |

| Young’s Modulus | $ E = \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon} $ | Stress (σ), Strain (ε) | Intrinsic material stiffness |

| Work-Energy | $ W = \Delta KE + \Delta PE + \Delta U $ | Kinetic (KE), Potential (PE), Internal (U) energy | Energy transfer/transformation |

| Conservation of Energy | $ mgh = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 $ | Mass (m), Height (h), Velocity (v) | PE → KE conversion |

| Power | $ P = \frac{W}{t} $ or $ P = Fv $ | Work (W), Time (t), Force (F), Velocity (v) | Rate of energy use |

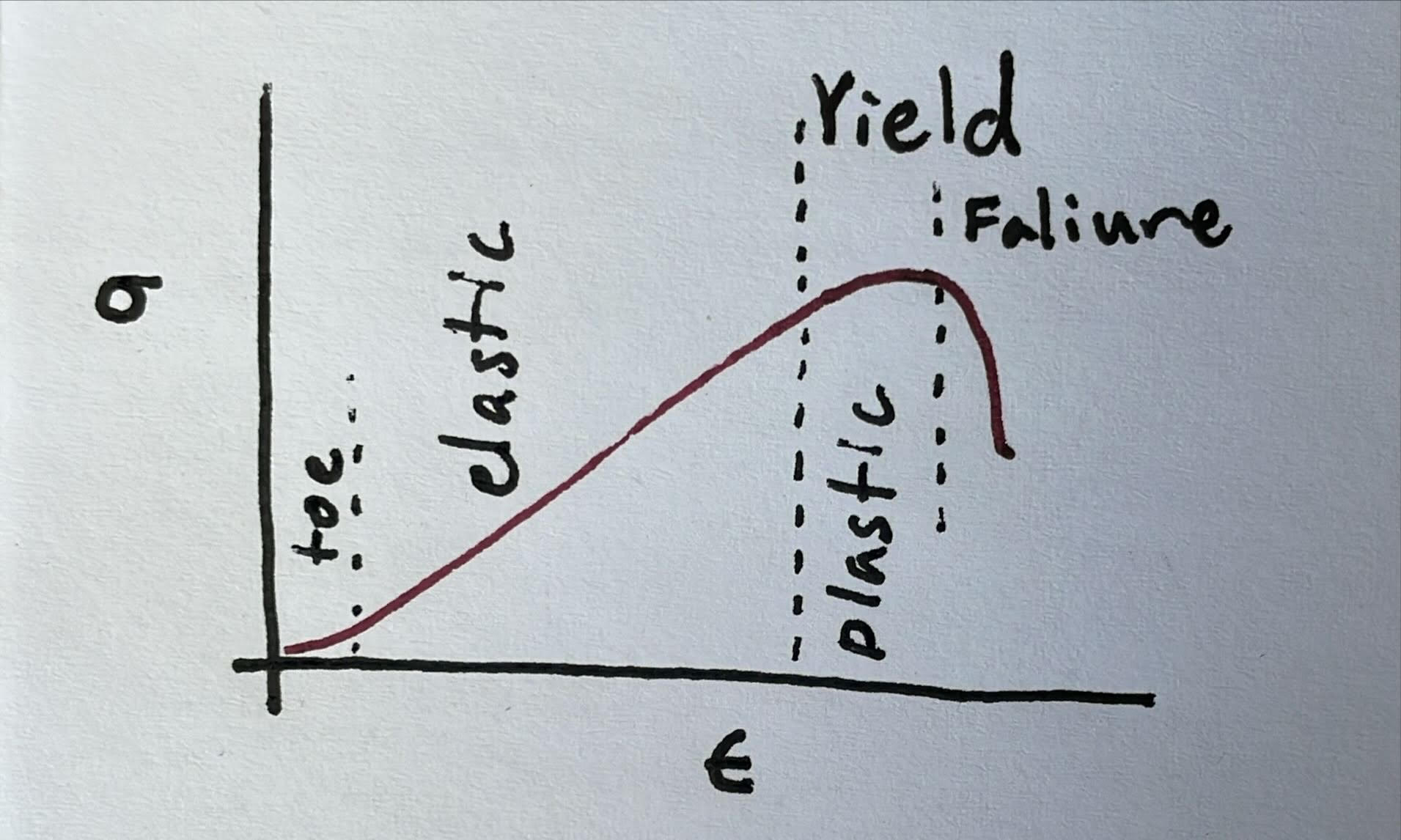

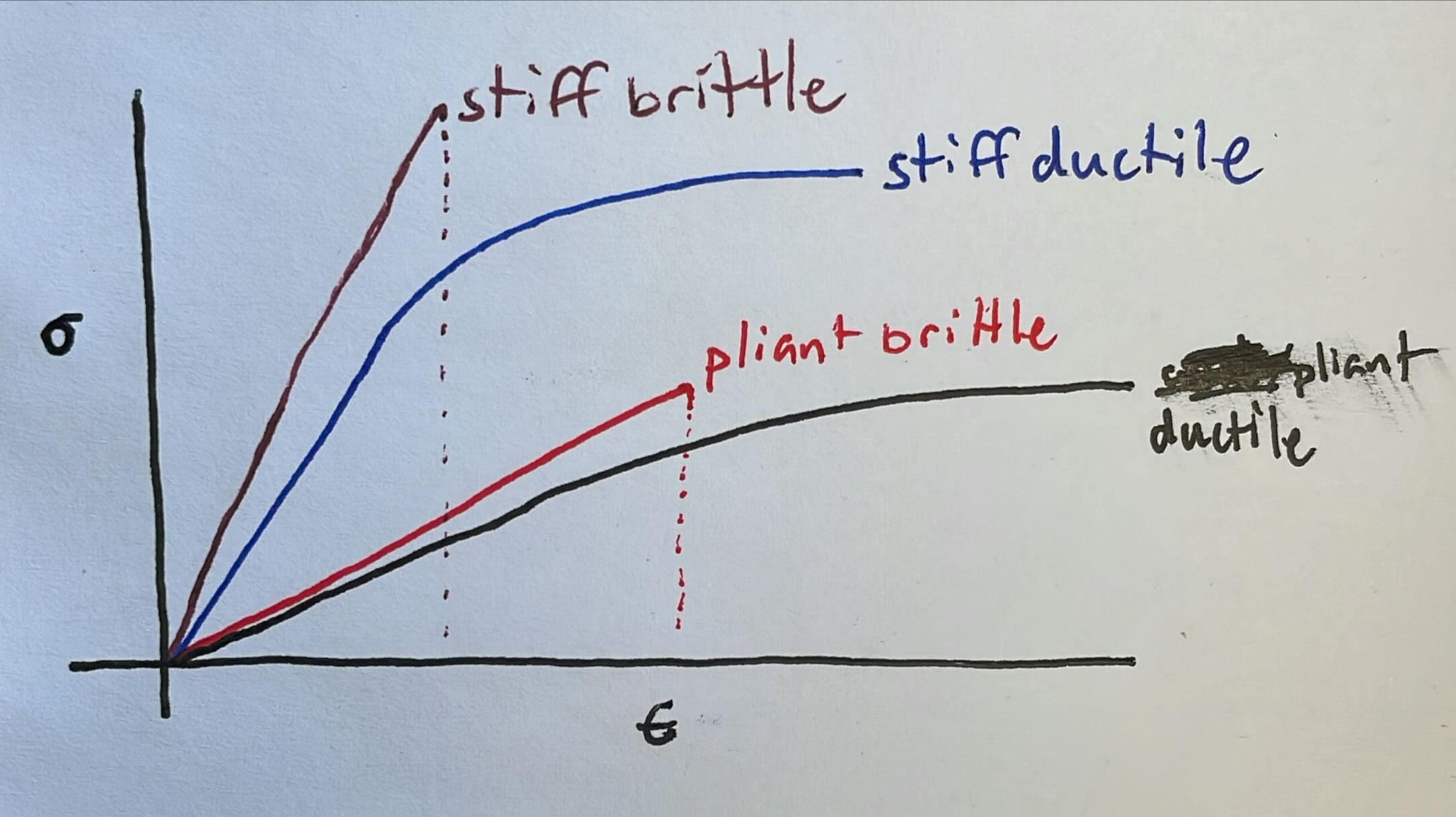

Plot This

Plot This Part Two

Rubber or viscoelastic materials show significant energy loss (as heat) when unloaded, resulting in a large loop between loading and unloading curves on a stress-strain plot. For example, a rubber band returns to its original shape after stretching but feels warm because energy was lost as heat, showing high hysteresis in its stress-strain loop.

When a material is held at a constant strain, stress gradually decreases over time due to molecular rearrangements, seen as a decaying exponential curve. For example, when a constant strain is applied to a viscoelastic material (e.g., chewing gum), the force-time curve shows an initial peak followed by a gradual decline as internal stresses relax over time.

Under constant load, a material slowly deforms over time. For example, a hanging rope under constant load slowly elongates over months; its length-time curve would show an initial elastic jump followed by a steady, time-dependent increase due to creep.

References

Week 13 Lecture, Montana State University, Department of Food Systems, Nutrition, & Kinesiology, Fall 2024.